Guest Contributor: Katie Sweeting

I grew up in the White suburbs of Los Angeles, in sunny Southern California, or as my dad liked to say, “the relatively smog-free western end of the San Fernando Valley.” I was a Valley Girl, for sure. I might have grown up racist if I didn’t have Richard and Claire O’Connell as parents.

Formative Years

Our family of five lived in Sepulveda and both of my parents were college professors—Dad taught psychology at Cal State Northridge and Mom taught English at Santa Monica College. They were card-carrying members of the NAACP and the Fair Housing Council, and Mom was active in the League of Women Voters. Two of my earliest memories from the early 1960s include eating TV dinners for a week while my mom mourned the assassination of President John Kennedy, and my sister moving into a commune after the disillusionment and despair resulting from witnessing the assassination of President Kennedy’s brother, Robert F. Kennedy (RFK). My sister worked on RFK’s campaign, and was a Bradley girl, working on the unsuccessful campaign of Tom Bradley in 1969. Mayor Tom Bradley became the first Black mayor of Los Angeles when he was elected four years later.

Sepulveda dealt with its own issues of racism. Sepulveda was largely White and Mexican-American. The western part of Sepulveda wanted to differentiate itself from the predominantly Mexican eastern part and renamed itself North Hills. Ironically, “six months after residents of part of Sepulveda changed their region’s name to North Hills–to escape the stigma of crime and seediness they said had become attached to the name–the community they fled rejoined them . . . What remained of Sepulveda will now be named North Hills too, Councilman Joel Wachs told a meeting Thursday night at Sepulveda Junior High School” (Jim Herron Zamora 22 Nov. 1991, LA Times).

First Black Friends

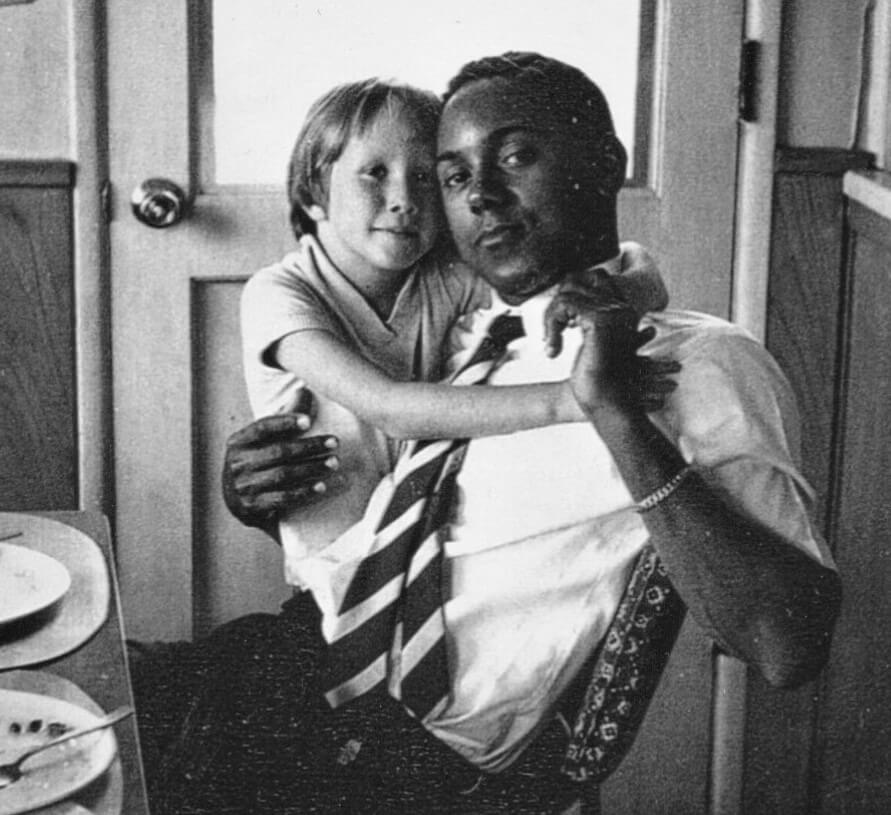

I grew up in a White suburb where most residents mistrusted Blacks and Latinos. While I don’t remember ever having a “talk” about race or racism, my parents accepted people from all backgrounds and races, demonstrating by their lives what it meant to be anti-racist. But they didn’t just model being anti-racist; they went out of their way to befriend Blacks and invite them into the family, to show me and my siblings that the pigment of one’s skin did not determine value or character, worth or beauty. My mom loved to start up conversations with strangers, so while checking out at Vons Grocery Store one day, she chatted up the young man bagging her groceries. Lewis Coleman was a young Black man from Alabama and after talking with him several times, Mom invited Lewis over for dinner. He eventually became a lifelong family friend, and I most recently saw him at my mom’s memorial service in 2016. I cannot overestimate his influence on me as a young White girl in a completely White neighborhood. He is funny, sweet, kind, and a real storyteller—my very positive first introduction to Black men. When he found out I married a Black man, he took some well-earned credit.

It wasn’t until college, at Cal State Northridge in 1977, that I had my first close Black girlfriend. Lydia was a classmate who lived in Watts. We became friends—she visited my house, and I visited her in Watts. Her single mom was raising several girls, some of whom had children of their own. Watts was a world away from where I lived in Sepulveda. Watts was predominantly Black, filled with families whose parents worked mainly in service industries. Lydia’s mom worked as a janitor in a hospital. Twelve years before I met Lydia, Watts erupted in the riots of 1965, precipitated by the treatment of Stepbrothers Marquette and Ronald Frye by White Highway Patrolmen and police officers. A gathering crowd and the brute force police exerted exacerbated the tense standoff and riots ensued. Here we are 55 years later still dealing with the same issues.

Lewis and Lydia opened my eyes to what it meant to live as a Black man and woman in America. My friendships with Lewis and Lydia opened my eyes to the history of trauma and systemic racism faced by Black Americans every day.

Husband and Sons

In 1979 I spent a summer in Kenya, East Africa on a short-term mission trip. There were 30 of us from the U.S. going to various parts of East Africa and I met a man named Bill Sweeting, the only African American in the group. I was attracted to his gregarious smile and raucous laughter. We became better acquainted over the summer and upon our return to New York City, Bill invited me to stay for a few days to see the sights and meet some of his family. Honestly, I was more nervous about walking around New York City for three days than I was about living in Kenya for three months. In 1979 1,733 murders were committed in NYC—the crime rate was astronomical. I stayed because I wanted to learn more about Bill and the city he called home. Four months later he flew out to LA to meet my parents—guess who’s coming to dinner!

I moved to New York in 1980 after I graduated from college, and Bill and I married in 1983. By the late 1990s we had a teen and pre-teen son, and when Amadou Diallo was shot 41 times and killed in 1999 by four white police officers when he reached for his identification, we did have “the talk” with our sons.

Twenty-one years later America is yet again facing its own racism—both individual and systemic. I will not pretend to posit a solution for systemic racism. I do, however, firmly believe that on an individual level, it is not enough to do nothing. It is not enough to not pass on racism to our children. It is not even enough to model good anti-racist behavior. We must actively, purposefully, consistently teach our children to be anti-racist. It starts with us, the parents. If you’re White, do you have a Black friend? Not an acquaintance, colleague, or neighbor—a real friend. If not, start there.

* * *

Katie Sweeting is an Associate Professor of English at Hudson County Community College in Jersey City, NJ. Her website is www.KatieSweeting.com